The privately run Rendikala Subong Museum in Mokokchung district has shut down permanently due to low footfall, financial constraints and lack of institutional support.

Share

Private cultural space built over four decades closes amid low footfall and financial constraints

DIMAPUR — The Rendikala Subong Museum in Mokokchung district has shut down permanently, bringing to an end a privately run cultural space built over decades through the personal efforts of its founder and sustained without institutional support.

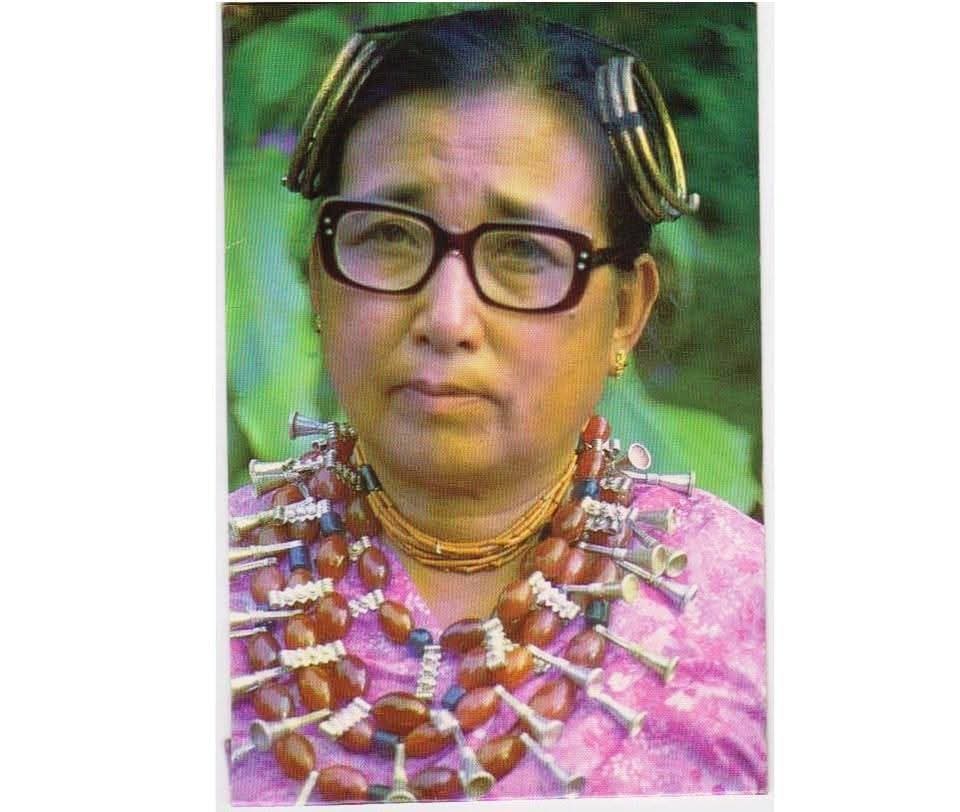

Founded by Rendikala Subong (1925–2006), the museum housed more than 700 artefacts collected from across Nagaland and beyond. Rendikala began collecting cultural objects in the 1960s and set up a mini museum in the 1970s, slowly expanding the collection over the years. In 2004, it was officially upgraded to the Rendikala Subong Museum and was later listed in the Nagaland Guide Book for students.

The collection included jewellery, earthen pots, traditional artefacts and ancestral wooden cots, many of them decades old and some dating back more than a century. Several pieces were inherited or sourced from different parts of the state. Among the rarer items was a nano-sized Bible, described as one of the smallest in the world, gifted to Rendikala by a friend from Germany.

According to her daughters, Rendikala established the museum with the aim of familiarising younger generations with Naga traditions and culture, particularly those of the Ao community. The museum did not charge an entry fee and functioned for years solely on voluntary donations placed in a charity box.

Following Rendikala’s death in 2006, the museum was temporarily closed and later handed down to her daughters, including Amenla Wati and her five sisters. After renovations, the family decided to reopen the museum in 2022, hoping to revive their mother’s vision and reintroduce the space as a learning resource.

Speaking to Eastern Mirror, Amenla Wati said that in earlier years visitors were largely school groups and tourists who located the museum through the Nagaland Guide Book. Since its reopening, however, only three to four schools have visited the museum for educational purposes.

The family announced the permanent closure of the museum this year, citing low footfall, financial constraints and the absence of external support. Atola Subong said the museum had been run entirely as a personal initiative, without any assistance from the government.

“If we were financially strong enough, we would have run it,” she said.

Explaining the decision to sell the collection, Atola Subong said the family did not want the artefacts to deteriorate due to neglect and decided instead to pass them on to people they believed would preserve them. She said the family was confident that those who had already purchased some pieces would take care of them.

-1768322936439.jpeg&w=1200&q=75)

Amenla Wati said her advancing age, the physical demands of maintaining the museum and the fact that her surviving siblings live outside Nagaland made collective management increasingly difficult.

Recalling her grandmother, one of Rendikala’s granddaughters, Aben, said she remembered her ‘otsü’, grandmother in the Ao dialect, as a relaxed and forward-thinking person. She said Rendikala enjoyed travelling and would visit the family when they were living in Bihar, carrying bags filled with local products from Nagaland.

“We used to write her letters and ask for things from home. She would always send us cartons full of sour candies and local ingredients,” Aben said.

She added that she only later understood remarks often made by her mother and aunts that Rendikala was ahead of her time. “In a male-dominated time, she did things which some of us cannot even imagine. She thought about future generations and wanted to showcase and preserve our culture,” she said.

-1768322970116.jpeg&w=1200&q=75)

Aben said it was difficult to see something her grandmother had worked so hard to build come to an end. “I wish we could do more, but we cannot take care of it due to lack of resources and manpower,” she said.

Atola Subong said the decision to close the museum was taken with reluctance, as keeping the artefacts packed away went against their mother’s wishes. “We felt sad because our mother’s desire was not fulfilled,” she said.