The Japan Junior Orchestra, led by Minami Shinichi, found cultural and musical connection in Nagaland during performances and community visits.

Share

KOHIMA — In 1983, the city of Ōta in Gunma Prefecture, Japan, was known as a place with “no music,” recalled Minami Shinichi, General Music Director of the Japan Junior Orchestra Association.

Once a centre for aircraft production during the Second World War and later a car manufacturing hub, Ōta was a working-class city where music had little presence. That year, Minami, a Tokyo-born musician, began travelling regularly to teach music in Ōta’s schools. Over time, his students became teachers themselves. But Minami wanted more than classroom instruction; he wanted an orchestra.

The idea of starting a junior orchestra in Gunma drew surprise. While orchestras existed in Japan’s larger cities, Gunma had none. “People were not interested in music then,” he said.

Four decades later, Minami’s effort has grown into a global movement. At 72, he has helped establish 25 junior orchestras across Japan, and he has left footprints in more than a dozen countries, including India.

Minami first visited Nagaland in August 2025 and returned during the Hornbill Festival, leading the Japan Junior Orchestra in performances across several venues.

Also read: Hornbill Festival 2025 concludes with new global and regional partnerships

For him, music is not a business but a voluntary mission to harmonise the world — a philosophy shaped during his studies at the University of Music and Performing Arts, Vienna, from 1972 to 1977.

There, the then 20-year-old studied clarinet, piano and conducting, and dreamt of performing with his students at Vienna’s Golden Hall — the same stage associated with Beethoven. That dream materialised in 2005, and again in 2013 and 2019.

Minami’s visit to Nagaland also carried historical weight. In Japan, the Battles of Imphal and Kohima during the Second World War remain sombre chapters. For decades, most Japanese visitors to the region were families of soldiers who had died there.

“The history of Japanese soldiers coming to this town 81 years ago — I felt there was something connected to me,” Minami said. He added that the people of Kohima reminded him of the Japanese in their kindness and seriousness.

At the same time, he noted everyday challenges — the cold weather, limited heating, spicy food, and narrow, steep roads — all of which were unfamiliar.

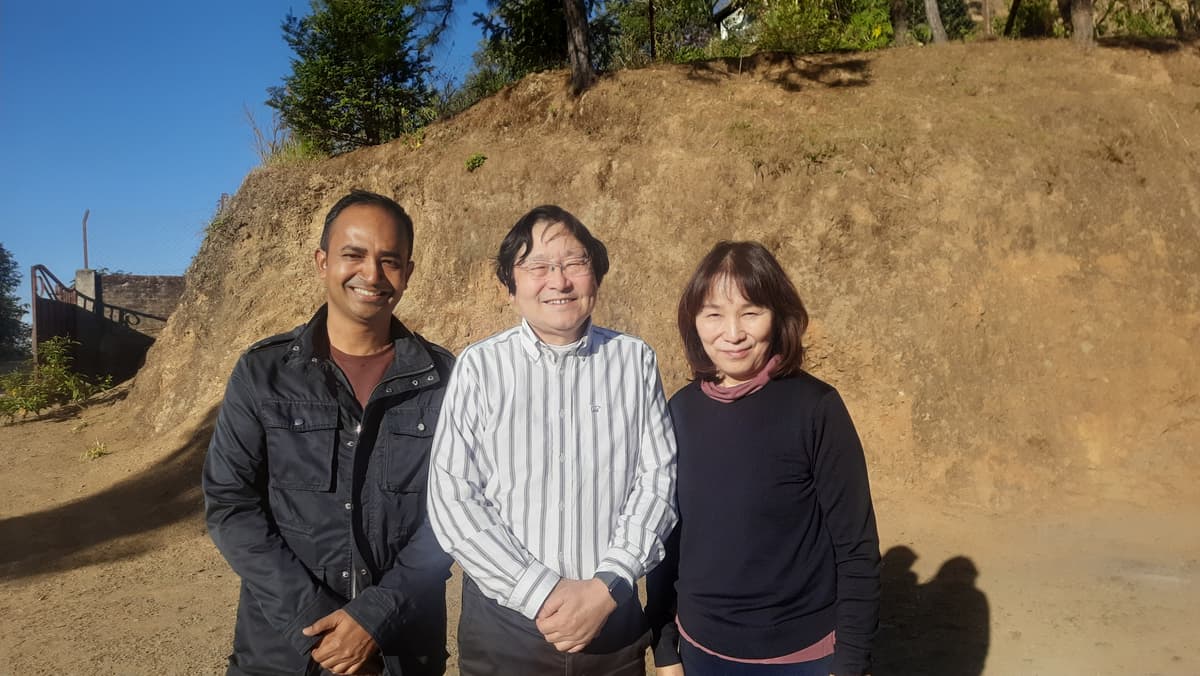

The journey to Nagaland came through Minami’s long-time friend Manab Naskar, a cellist currently teaching at the Nagaland College of Music and Fine Arts, Kohima.

Naskar, originally from West Bengal, had never visited Nagaland before taking up the post. It was through musician Zapocho Tetseo, whom he met in Nepal a decade earlier, that the visit was coordinated.

Together with other orchestra members, Minami and Naskar performed extensively during the Hornbill Festival, sharing stages with local musicians.

Beyond formal performances, the group also visited ZAVMAST Children Home in Khulazu Basa village, where they conducted music lessons and donated instruments.

Naskar said he values working with Minami because of his commitment to reaching communities in developing regions. As a Christian, he said the shared faith helped strengthen their connection. Naskar is also part of Minami’s orchestra.

“I do a lot of volunteer work when I get free time. I believe that music is a gift that you get from God himself. When the gift is given to you, you don't keep it, you share it with people,” he said.

While acknowledging the musical talent among Nagas, Naskar said structured training and guidance remain essential. He noted the lack of strong string orchestras in the region and said Minami hopes to help build something lasting.

Orchestra member China Uehara said she was deeply moved by the warmth and openness of the people. “Like all of you, I want to become a kind adult who can take action for the sake of others,” she said.

Yoko Harada said she noticed cultural similarities between Japan and Nagaland, particularly in modesty and quiet public spaces. She observed that people in Kohima smiled easily, which she felt reflected honesty and openness. “I look forward to the day when I can see those smiles again,” she said.

For Sakura Akiyama, the few days in Nagaland became an “important memory.” She admitted initial uncertainty about how local audiences would receive unfamiliar musical genres and instruments such as the erhu.

“When I stood on the stage at the Hornbill Festival and heard the cheers, I was deeply moved,” she said, adding that she would never forget being gifted a locally made necklace by a girl after her performance.

She also described staying at the Nagaland College of Music and Fine Arts, where the group practised and performed during Christmas events.

“We became friends in no time. I have experienced it in many countries, but I once again realised that music easily jumps over borders and language barriers,” Akiyama said.

Yuko Arafune, who documented the visit with her husband, said she was struck by the friendliness of the people and the visible confidence of women.

“I’ve noticed that women feel empowered to voice their own opinions. In Japan, we often feel the need to reserve our thoughts to maintain harmony.

I’m not sure if it’s due to education or culture, but women here seem to have more dreams and ambitions compared to those in Japan,” she observed.

Perhaps Minami’s belief in music as a source of joy shaped by a difficult childhood in Japan — and his experience of building friendships across the world through music — is what drew him to Nagaland. As he put it, “Music is very important for life, and I want to support more.”