Nagaland’s 1098 Childline offers 24/7 support for children in distress, with dedicated teams working across districts.

Share

KOHIMA — Beyond the simple four-digit number, the 1098 Child Helpline (CHL) in Nagaland represents round-the-clock commitment to receiving distress calls, intervening and ultimately saving children.

Since its inception on September 1, 2023, Child Helpline 1098 Nagaland has received a total of 11,364 calls. As of May 2025, it had intervened in 1,398 of them.

The categories included lost and found, abused children, giving emotional support, counselling, and guidance, as well as family-related issues.

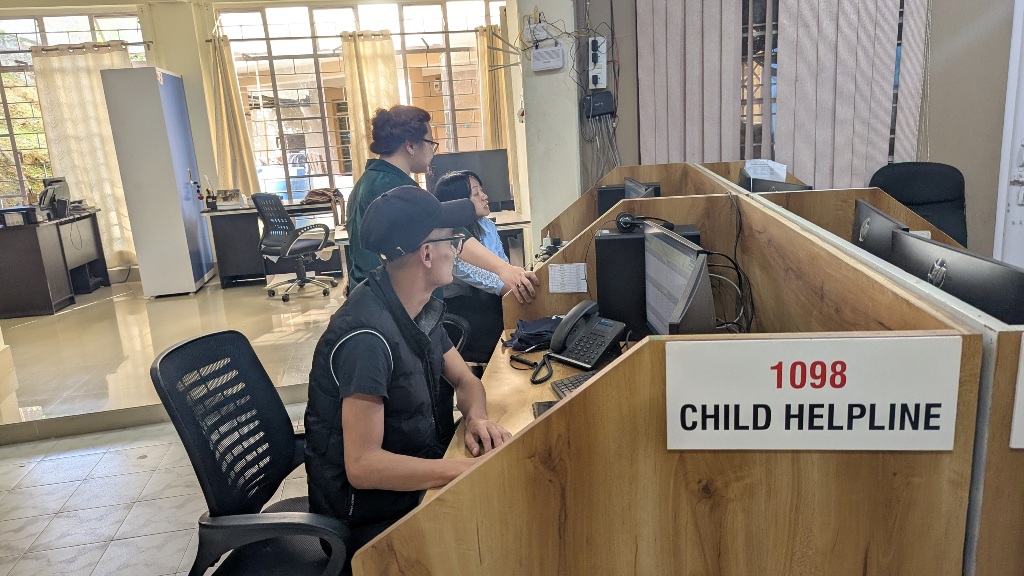

The well-equipped Women and Child Development Control Room serves as a centre for both the 1098 Child Helpline and the 181 Women Helpline. It is located in the office of Nagaland State Social Welfare Board and Mission Shakti under Social Welfare Department, Kohima.

The national toll-free child helpline 1098 is also functioning in 16 districts of Nagaland. The services would soon be introduced in Pochury, the newest district of the state.

Also read: Education as a pretext: Hidden faces of child labour in Nagaland

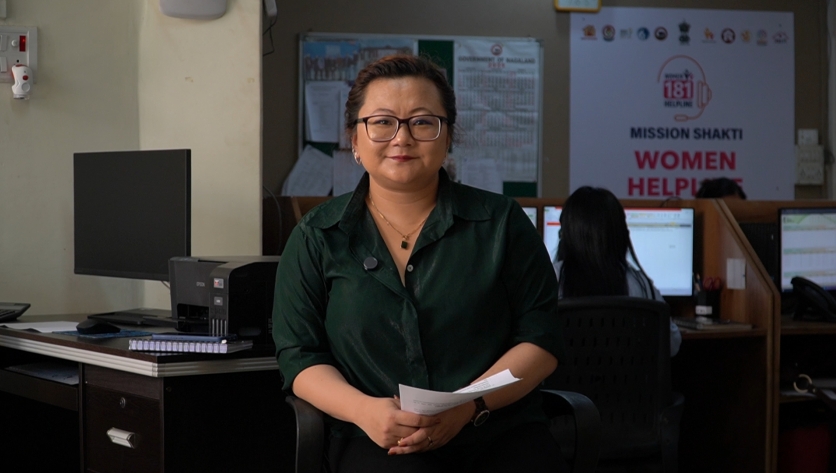

In an interview with Eastern Mirror, Neingutuonuo Kulnu, administrator of Child Helpline-Women and Child Development Control Room Nagaland, gave a detailed insight into the operations of the 1098 Child Helpline in Nagaland. They work with children aged 0 to 18 years and deal with children in conflict with the law (CCL/CICL) as well as children in need of care and protection (CNCP).

They intervene in cases like lost and found, missing children, child abuse—emotional, sexual and physical—and others.

Prior to September 1, 2023, the service was running as Childline under a non-governmental organisation. The head office for the Northeast states was in Kolkata. However, the ministry introduced state-specific services, and each state, including Nagaland, now has its own Women and Child Development control room.

Public awareness challenges

One of the major challenges they face is the lack of awareness within the community. During distress calls and interventions, they often encounter resistance, making it difficult to validate the importance of their work.

She added the team is legally bound and has to follow a legal format, supported by the Juvenile Justice Act. For them, there is a given timeline for everything, including intervention.

“When we intervene in cases, people often feel we’re ‘barging into their homes’ or overstepping boundaries,” she said. “We’re frequently met with hostility—people asking, ‘Who do you think you are?’”

“As the first response team, we end up absorbing much of the community’s anger. When incidents occur, we face immense pressure and, in some cases, even receive threats,” she added.

Despite these challenges, she reflected on the deeper purpose of their work with children: “At the end of the day, I believe each of us is a guardian in one way or another.”

These numerous challenges notwithstanding, the Childline team in Nagaland remains steadfast in its mission. Whether it's responding to distress calls, rescuing children, or gathering crucial details to hand over cases to the Child Welfare Committee (CWC), the team presses on.

According to Kulnu, seeing a child return to a safe and peaceful environment is their greatest motivation.

Collaborative efforts

The CHL does not work in isolation. Its works are made possible through coordination with the district child helpline.

The intervention process begins with the police, followed by critical support from the Child Welfare Committee (CWC), Juvenile Justice Board (JJB), legal services and Health department, and other allied services—all those have to come together and bring a case to a meaningful conclusion—one that serves the best interest of the child and ensures their safety.

Behind the helpline number 1098 is a team of dedicated professionals available round-the-clock for children in distress. In Kohima’s control room, 13 operators work in three shifts—morning, day, and night—ensuring no call goes unanswered.

At the district level, the Child Helpline team comprises a project coordinator, a counsellor, three supervisors, and three case workers. The staff from both the control room and the district unit work in close coordination to handle each case that comes in.

“We never know when a call will come—maybe at midnight—and we must be ready to intervene at any moment,” Kulnu said. “Even on Christmas or New Year, the work doesn’t stop. It’s 24/7.”

Personal mission

For Kulnu, working with children isn’t just a job—it’s a calling. While pursuing her master’s degree, she realised that her passion lay in working with women or children. A chance opportunity during a six-month break introduced her to Childline through a local NGO, and there was no turning back.

“I felt like it was meant to be,” she said. “As I got involved, I felt myself getting closer to the community each day.”

Having worked with children for six to seven years now, she believes that truly understanding a child requires becoming like one.

Kulnu urged the public to dial 1098 whenever they come across a child in distress. “We’re always here, waiting for that one call that could change a child’s life,” she said.